Our Legacy

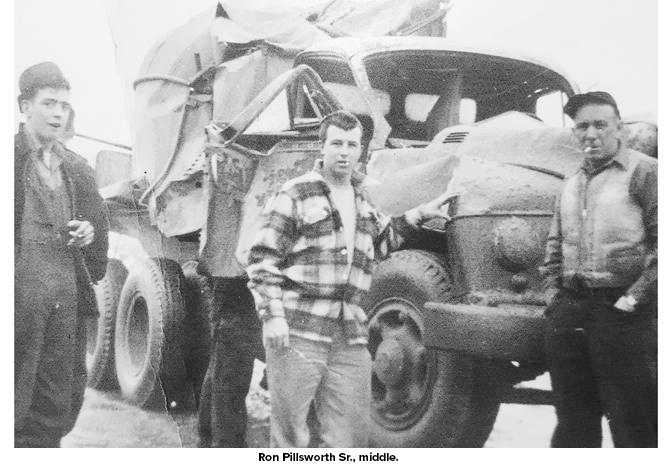

Honouring Ron Pillsworth Sr.

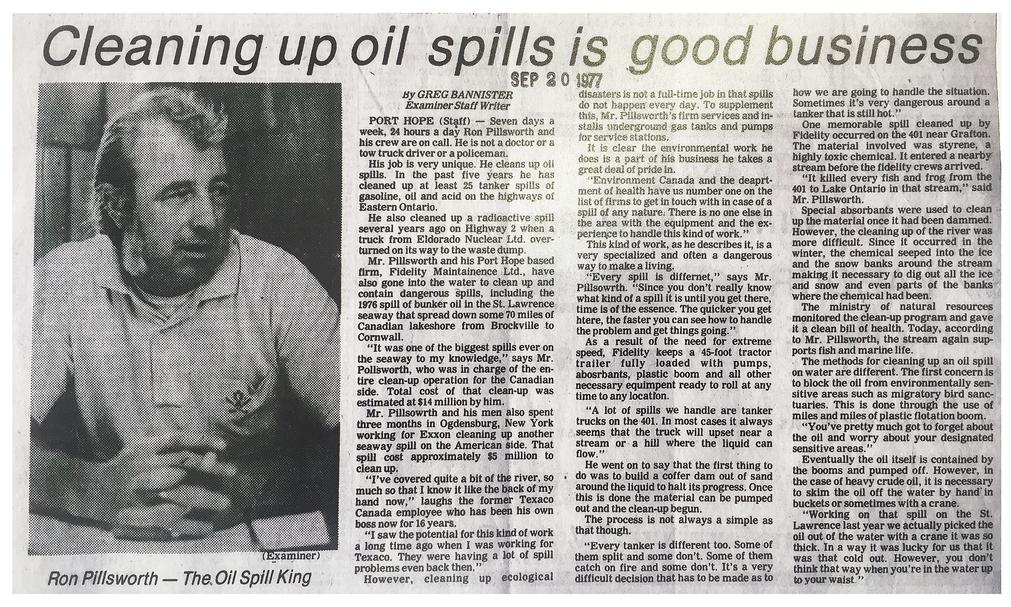

As a 3rd generation contractor, Jim Pillsworth incorporated Fidelity Engineering & Construction in 2013, and as such continued the legacy of the Fidelity name to pay homage to his grandfather, the late Ron Pillsworth Sr. known to many as the “The Oil Spill King” and founder of Fidelity Maintenance.

Cleaning up oil spills is good business

September 20, 1977

By Greg Bannister – Examiner Staff Writer

PORT HOPE (Staff) – Seven days a week, 24 hours a day, Ron Pillsworth and his crew are on call. He is not a doctor or a tow truck driver or a policeman.

His job is very unique. He cleans up oil spills. In the past five years he has cleaned up at least 25 tanker spills of gasoline, oil and acid on the highways of Eastern Ontario.

He also cleaned up a radioactive spill several years ago on Highway 2 when a truck from Eldorado Nuclear Ltd. over-turned on its way to the waste dump site.

Mr. Pillsworth and his Port Hope based firm, Fidelity Maintenance Ltd., have also gone into water to clean up and contain dangerous spills, including the 1976 spill of bunker oil in the St. Lawrence seaway that spread down some 70 miles of Canadian lakeshore from Brockville to Cornwall.

“It was one of the biggest spills ever on the seaway to my knowledge,” says Mr. Pillsworth, who was in charge of the entire clean-up operation for the Canadian side. Total cost of that clean-up was estimated $14 million by him.

Mr. Pillsworth and his men also spent three months in Ogdensburg, New York working for Exxon cleaning up another seaway spill on the American side. That spill cost approximately $5 million to clean up.

“I’ve covered quite a bit of the river, so much so that I know it like the back of my hand now,” laughs the former Texaco Canada employee who has been his own boss now for 16 years.

“I saw the potential for this kind of work a long time ago when I was working for Texaco. They were having a lot of spill problems even back then.”

However, cleaning up ecological disasters is not a full-time job in that spills do not happen every day. To supplement this, Mr. Pillsworth’s firm services and installs underground gas tanks and pumps for service stations.

It is clear the environmental work he does is a part of his business he takes a great deal of pride in.

“Environment Canada and the department of health have us number one on the list of firms to get in touch with in case of a spill of any nature. There is no one else in the area with the equipment and the experience to handle this kind of work.”

This kind of work, as he describes it, is a very specialized and often dangerous way to make a living.

“Every spill is different,” says Mr. Pillsworth. “Since you don’t really know what kind of a spill it is until you get there, time is of the essence. The quicker you get there, the faster you can see how to handle the problem and get things going.”

As a result of the need for extreme speed, Fidelity keeps a 45-foot tractor trailer fully loaded with pumps, absorbents, plastic boom and all other necessary equipment ready to roll at any time to any location.

“A lot of spills we handle are tanker trucks on the 401. In most cases it always seems that the truck will upset near a stream or a hill where the liquid can flow.”

He went on to say that the first thing to do was to build a coffer dam out of sand around the liquid to halt its progress. Once this is done the materials can be pumped out and clean-up begun.

The process is not always a simple as that though.

“Every tanker is different too. Some of them spill and some don’t. It is a very difficult decision that has to be made as to how we are going to handle the situation. Sometimes it’s very dangerous around a tanker that is still hot.”

One memorable spill cleaned up by Fidelity occurred on the 401 near Grafton. The material involved was styrene, a highly toxic chemical. It entered a nearby stream before Fidelity crews arrived.

“It killed every fish and frog from the 401 to Lake Ontario in that stream,”

said Mr. Pillsworth.

Special absorbents were used to clean up the material once it had been dammed. However, the cleaning up of the river was more difficult. Since it occurred in the winter, the chemical seeped into the ice and snow banks around the stream making it necessary to dig out all the ice and snow and even parts of the banks where the chemical had been.

The ministry of natural resources monitored the clean-up program and gave it a clean bill of health. Today, according to Mr. Pillsworth, the stream again supports fish and marine life.

The methods for cleaning up an oil spill on water are different. The first concern is to block the oil from environmentally sensitive areas such as migratory bird sanctuaries. This is done through the use of miles of plastic flotation boom.

“You’ve pretty much got to forget about the oil and worry about your designated sensitive areas.”

Eventually the oil itself is contained by the booms and pumped off. However, in the case of heavy crude oil, it is necessary to skim the oil off the water by hand in buckets or sometimes with a crane.

“Working on that spill in the St. Lawrence last year we actually picked the oil out with a crane it was so thick. In a way it was lucky for us that it was cold out. However, you don’t think that way when you’re in the water up to your waist.”